Ahora se pronostica que la temporada de huracanes del Atlántico de 2023 será más activa que el promedio a pesar de El Niño, pero también más impredecible, según las últimas perspectivas.

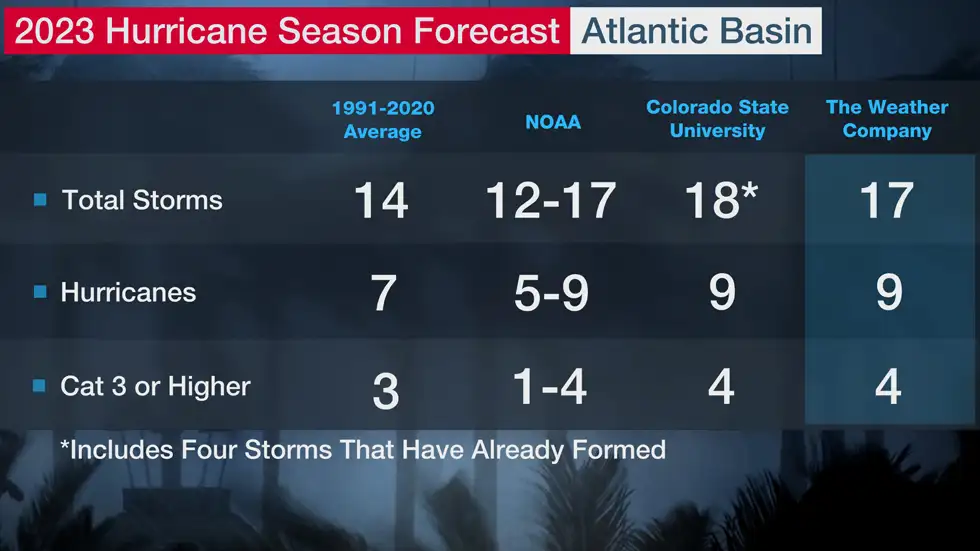

Una actualización publicada el jueves por el equipo de pronóstico tropical de la Universidad Estatal de Colorado prevé 18 tormentas, nueve de las cuales se espera que se conviertan en huracanes y cuatro de las cuales alcanzarán al menos la categoría 3.

Este es un aumento de tres tormentas, dos huracanes y un gran huracán desde su pronóstico anterior, que se publicó a principios de junio. El aumento de tormentas y el panorama general tiene en cuenta cuatro tormentas que ya han ocurrido este año.

Otras actualizaciones de pronósticos recientes se pueden encontrar a continuación, incluidas las de NOAA, The Weather Company y Atmospheric G2.

Arlene, Bret y Cindy se formaron en junio, y en enero se desarrolló una tormenta subtropical sin nombre que fue mejorada retroactivamente por el Centro Nacional de Huracanes en mayo.

La cuarta tormenta de la temporada no suele llegar hasta mediados de agosto, según el NHC.

Los historiales de seguimiento de las tormentas de la temporada de huracanes del Atlántico de 2023 al 6 de julio de 2023.

(Datos de seguimiento: NOAA/NHC)

Dos factores principales están en juego en esta temporada de huracanes: un fortalecimiento de El Niño y temperaturas extremadamente cálidas del agua del Atlántico.

El calor del océano Atlántico está fuera de serie

Uno de esos factores está dominando en este momento.

Un factor importante que contribuyó al mes de junio más cálido registrado en el planeta fue el calor récord de junio en la cuenca del Atlántico, donde se forman huracanes y tormentas tropicales.

«Este calor anómalo es la razón por la cual el pronóstico de huracanes estacionales de CSU ha aumentado, a pesar de (a) un El Niño probablemente robusto», escribió Phil Klotzbach, científico tropical y líder del equipo de pronóstico de CSU, en un tuit.

Esto es importante porque suponiendo que otros factores sean iguales, cuanto más profunda y cálida sea el agua del océano, más fuerte puede volverse una tormenta o un huracán.

Por lo general, hay una bolsa de agua más fría al principio de la temporada de huracanes desde las Islas de Cabo Verde hasta las Bermudas y el norte de las Islas de Sotavento. Las olas tropicales que llegan a esta bolsa de aguas más frías a menudo sucumben a condiciones hostiles.

Este calor que estamos viendo en este momento es más típico de agosto con mucho tiempo para un calentamiento adicional.

Esta agua inusualmente cálida para junio fue un factor detrás del desarrollo de las tormentas tropicales Bret y Cindy, la primera vez que se desarrollaron dos tormentas sobre la franja del Océano Atlántico entre África y las Antillas Menores en junio.

Pero, ¿qué pasa con El Niño?

Otro factor podría tener el efecto contrario de las cálidas aguas del Atlántico.

Las aguas ecuatoriales del Pacífico habían estado más frías que el promedio durante las últimas tres temporadas de huracanes, una condición conocida como La Niña. Pero esa Niña de larga duración finalmente desapareció.

An El Niño fue declarado a principios de junio y podría volverse fuerte en el corazón de la temporada de huracanes: agosto a octubre.

La razón por la que esta franja de agua alejada de la cuenca del Atlántico es importante es que es una de las influencias más fuertes en la actividad de la temporada de huracanes.

En las temporadas de huracanes de El Niño, a menudo se producen vientos cortantes más fuertes al menos sobre el Mar Caribe y algunas partes adyacentes de la cuenca del Atlántico. Esto tiende a limitar el número y la intensidad de tormentas y huracanes, especialmente si El Niño es más fuerte, como investigamos en un artículo de marzo.

Sin embargo, dado que este El Niño aún se encuentra en sus etapas iniciales, aún no ha ejercido fuerza en el patrón climático descrito anteriormente, pero puede hacerlo cada vez más durante el resto de la temporada de huracanes.

«(A) la alta probabilidad de un fuerte El Niño es la razón por la cual el pronóstico de huracanes de CSU no es para aún más actividad dado (a) un Atlántico cálido récord», escribió Klotzbach en otro Tweet.

Un equipo de pronóstico de The Weather Company y Atmospheric G2 también notó una tendencia en las temporadas de huracanes de El Niño de menos tormentas en el Golfo de México y más tormentas que se enroscan hacia el norte, luego hacia el noreste hacia el Océano Atlántico abierto o impactan partes de la costa este.

Eso se debe a que la altura de las Bermudas tiende a ser más débil, y también se debe a una disminución más persistente de los vientos en los niveles altos en el sureste de los EE. UU. durante El Niño, según el equipo de pronóstico de TWC/AG2.

Un patrón típico «recurvo» que puede presentarse en la temporada de huracanes.

Dados estos dos factores en competencia, un escenario plausible para el resto de la temporada de huracanes es que haya más tormentas en el este y centro del Océano Atlántico, alimentándose del agua inusualmente cálida, pero tal vez menos en el Mar Caribe y el Golfo de México, suponiendo que sean más hostiles. La cizalladura del viento de El Niño se pone en marcha.

The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season is now forecast to be more active than average despite an El Niño, but also more unpredictable, according to the latest outlook.

An update released Thursday by the Colorado State University tropical forecast team calls for 18 storms, nine of which are expected to become hurricanes and four of which will reach at least Category 3 status.

This is an increase of three storms, two hurricanes and one major hurricane since their previous outlook, which was released in early June. The increase in storms and the overall outlook takes into account four storms that have already occurred this year.

Other recent forecast updates can be found below, including those from NOAA, as well as The Weather Company and Atmospheric G2.

Arlene, Bret and Cindy formed in June, and an unnamed subtropical storm developed in January that was retroactively upgraded by the National Hurricane Center in May.

The fourth storm of the season doesn’t typically arrive until mid-August, according to the NHC.

Two major factors are in play this hurricane season: a strengthening El Niño and extremely warm Atlantic water temperatures.

Atlantic Ocean Warmth Is Off The Charts

One of those factors is dominating right now.

A major contributor to the planet’s hottest June on record was record June warmth in the Atlantic Basin where hurricanes and tropical storms form.

«This anomalous warmth is why CSU’s seasonal hurricane forecast has increased, despite (a) likely robust El Niño,» wrote Phil Klotzbach, tropical scientist and lead of the CSU forecast team, in a tweet.

Klotzbach noted the scope and magnitude of this anomalous warmth as of late June was well beyond what was seen in other warm ocean hurricane seasons such as 2020, 2010, 2005, 1998 and 1995.

This is important because assuming other factors are equal, the deeper and warmer the ocean water, the stronger a storm or hurricane can become.

Typically, there is a cooler pocket of water early in hurricane season from the Cabo Verde Islands to Bermuda to the northern Leeward Islands. Tropical waves reaching this pocket of colder waters often succumb to otherwise hostile conditions.

This warmth we’re seeing right now is more typical of August with plenty of time for additional warming.

This unusually warm water for June was one factor behind the development of tropical storms Bret and Cindy, the first time two storms developed over the strip of the Atlantic Ocean between Africa and the Lesser Antilles in June.

But What About El Niño?

Another factor could have the opposite effect of the warm Atlantic waters.

Pacific equatorial waters had been cooler than average during the past three hurricane seasons – a condition known as La Niña. But that long-lasting La Niña finally disappeared.

An El Niño was declared in early June and could become strong by the heart of the hurricane season: August through October.

The reason this strip of water far from the Atlantic Basin matters is that it’s one of the strongest influences on hurricane season activity.

Advertisement

In El Niño hurricane seasons, stronger shearing winds often occur over at least the Caribbean Sea and some adjacent parts of the Atlantic Basin. This tends to limit the number and intensity of storms and hurricanes, especially if the El Niño is stronger, as we investigated in a March article.

However, since this El Niño is still in its early stages, it hasn’t yet flexed its muscle on the weather pattern described above, but may do so increasingly during the remainder of the hurricane season.

«(A) high chance of a robust El Niño is why CSU’s hurricane forecast is not for even more activity given (a) record warm Atlantic,» wrote Klotzbach in another Tweet.

A forecast team at The Weather Company and Atmospheric G2 also noted a tendency in El Niño hurricane seasons for fewer Gulf of Mexico storms and more storms to either curl north, then northeast out into the open Atlantic Ocean or to impact parts of the East Coast.

That’s because the Bermuda high tends to be weaker, and it’s also due to a more persistent dip in the upper-level winds in the southeastern U.S. during El Niños, according to the TWC/AG2 forecast team.

Given these two competing factors, one plausible scenario to the rest of the hurricane season is more storm tracks in the eastern and central Atlantic Ocean, feeding off the unusually warm water, but perhaps fewer in the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, assuming more hostile wind shear from El Niño kicks into gear.

Prepare The Same Every Hurricane Season

What these outlooks cannot tell you is whether or not your area will get struck this season and when that might happen.

A season with fewer storms or hurricanes can still deliver the one storm that makes a season destructive or devastating.

In 2015, one of the strongest El Niños on record reduced the hurricane tally to four that season. However, one of those was Joaquin, which devastated the central Bahamas.

And it doesn’t take a hurricane to be impactful, especially regarding rainfall flooding.

Also in the 2015 season, Tropical Storm Erika was ripped apart by wind shear and dry air near the Dominican Republic. But before that happened, it triggered deadly and destructive flooding in Dominica.

weather.com