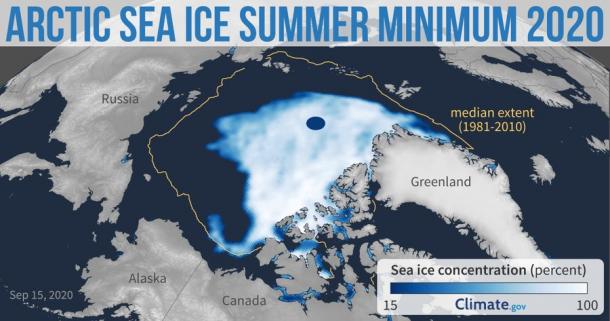

Arctic sea ice – a key climate change indicator – has reached its annual minimum extent after the summer melt season. It was the second lowest extent only after the record low observed in 2012.

The U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) announced that on 15 September, sea ice extent was 3.74 million square kilometers (1.44 million square miles). The Alfred Wegener Institute Institute confirmed this reading, with figures from the University of Bremen saying it was 3.8 million square km. Other space agencies and data providers, for example EUMETSAT Ocean and Sea Ice Satellite Application Facility (OSI SAF) and Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) concur that the second lowest sea-ice extent was reached this year.

The 2020 figure—preliminary because a late-season surge of summer warmth could still drop the extent further—continued an observed trend of long-term Arctic sea ice decline.

The last 14 years—2007 to 2020—have the lowest 14 minimum extents of the 42-year satellite record.

There are a number of causes for the massive loss of ice this summer. This includes extremely high air and water temperatures. Accordingly, heat impacted the ice from both above and below, resulting in widespread melting.

A record-breaking heatwave and unprecedented wildfires in Siberia were a major contributing factor during a northern hemisphere summer which will leave a deep wound in the cryosphere, with major impacts on ice shelves and glaciers in the northern hemisphere.

“It’s been a crazy year up north, with sea ice at a near-record low, 100-degree (Fahrenheit) heat waves in Siberia, and massive forest fires,” said Mark Serreze, director of NSIDC. “The year 2020 will stand as an exclamation point on the downward trend in Arctic sea ice extent. We are headed towards a seasonally ice-free Arctic Ocean, and this year is another nail in the coffin.”

“This threshold means the Arctic is more ocean than ice, a blue highway that’s been open since mid-July and won’t close until well into October,” said Ted Scambos, senior research scientist at the Earth Science Observation Center at the University of Colorado-Boulder.

“This threshold means the Arctic is more ocean than ice, a blue highway that’s been open since mid-July and won’t close until well into October,” said Ted Scambos, senior research scientist at the Earth Science Observation Center at the University of Colorado-Boulder.

Temperatures in the Arctic are rising more than twice as fast as the global average. Unique amplification processes and feedbacks, such as the rapid decline of sea ice, significantly contribute to this warming. The consequences of a warming Arctic will be far-reaching across the northern hemisphere.

The fast-warming Arctic has started to transition from a predominantly frozen state into an entirely different climate, according to a comprehensive new study of Arctic conditions by scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

«The rate of change is remarkable,» said NCAR scientist Laura Landrum, the lead author of the study published in Nature Climate Change. «It’s a period of such rapid change that observations of past weather patterns no longer show what you can expect next year. The Arctic is already entering a completely different climate than just a few decades ago.»

In the new study, Landrum and her co-author, NCAR scientist Marika Holland, find that Arctic sea ice has melted so significantly in recent decades that even an unusually cold year will no longer have the amount of summer sea ice that existed as recently as the mid-20th century. Autumn and winter air temperatures will also warm enough to enter a statistically distinct climate by the middle of this century, followed by a seasonal change in precipitation that will result in additional months in which rain will fall instead of snow.

Among long-time observers of Arctic sea ice, the 2020 value was significant in that it not only punctuated a long-term decline, but also because it fell below the 4-million-kilometer (1.5-million-mile) threshold for only the second time in the satellite record—after 2012, when the minimum extent dipped to 3.39 million square kilometers (1.31 million square miles).

The exact time at which the sea ice reaches its absolute minimum depends on the weather conditions in the Arctic, and can only be determined once there is clear evidence that the sea-ice extent has begun to grow again. Based on past experience, this usually comes in mid-September, though sometimes not until the second half of the month.

The sea ice extent is measured by satellite data, including by NASA, the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) at the University of Colorado Boulder, AWI, the EUMETSAT OSI SAF, and JAXA-NiPR. Sea-ice extent is defined as the area where ice concentration is at least 15 percent.

The rapid ice melting was observed in detail by experts on board the German research icebreaker Polarstern, which is the central observatory for the most ambitious Arctic research expedition ever undertaken and involving scientists from 17 nations.

The rapid ice melting was observed in detail by experts on board the German research icebreaker Polarstern, which is the central observatory for the most ambitious Arctic research expedition ever undertaken and involving scientists from 17 nations.

“The scale of Arctic sea-ice retreat this year was breath-taking. Just a short time ago, when we reached the North Pole, we could see broad stretches of open water reaching nearly to the Pole, surrounded by ice that was riddled with holes produced by massive melting. The Arctic ice is disappearing at a dramatic rate. With the MOSAiC expedition, we’re investigating the underlying processes on site, and in more detail than ever before, so that we can accurately represent these rapid changes in the Arctic in our climate models,” says Expedition Leader Prof Markus Rex.

Polar Stern crossed in the geographic North Pole on 19 August, passing through the Fram Strait on the North-east side of Greenland in a region that used to be home to thick multi-year ice.

El hielo marino del Ártico, un indicador clave del cambio climático, ha alcanzado su extensión mínima anual después de la temporada de deshielo del verano. Fue la segunda extensión más baja solo después del mínimo histórico observado en 2012.

El Centro Nacional de Datos de Nieve y Hielo de EE. UU. (NSIDC) anunció que el 15 de septiembre, la extensión del hielo marino era de 3,74 millones de kilómetros cuadrados (1,44 millones de millas cuadradas). El Instituto Instituto Alfred Wegener confirmó esta lectura, con cifras de la Universidad de Bremen que dicen que fue de 3,8 millones de kilómetros cuadrados. Otras agencias espaciales y proveedores de datos, por ejemplo EUMETSAT Ocean and Sea Ice Satellite Application Facility (OSI SAF) y la Agencia de Exploración Aeroespacial de Japón (JAXA) coinciden en que este año se alcanzó la segunda extensión más baja de hielo marino.

La cifra de 2020, preliminar porque un aumento repentino del calor del verano al final de la temporada podría reducir aún más la extensión, continuó una tendencia observada de disminución a largo plazo del hielo marino del Ártico.

Los últimos 14 años, 2007 a 2020, tienen las 14 extensiones mínimas más bajas del récord de satélites de 42 años.

Hay varias causas de la pérdida masiva de hielo este verano. Esto incluye temperaturas extremadamente altas del aire y del agua. En consecuencia, el calor impactó el hielo tanto desde arriba como desde abajo, lo que provocó un derretimiento generalizado.

Una ola de calor récord e incendios forestales sin precedentes en Siberia fueron un factor importante que contribuyó durante un verano del hemisferio norte que dejará una herida profunda en la criosfera, con importantes impactos en las plataformas de hielo y los glaciares en el hemisferio norte.

“Ha sido un año loco en el norte, con hielo marino en un mínimo casi récord, olas de calor de 100 grados (Fahrenheit) en Siberia e incendios forestales masivos”, dijo Mark Serreze, director de NSIDC. “El año 2020 será un signo de exclamación sobre la tendencia a la baja en la extensión del hielo marino del Ártico. Nos dirigimos hacia un océano Ártico estacionalmente libre de hielo, y este año es otro clavo en el ataúd «.

Hielo marino Septiembre de 2020 «Este umbral significa que el Ártico es más océano que hielo, una carretera azul que ha estado abierta desde mediados de julio y no se cerrará hasta bien entrado octubre», dijo Ted Scambos, científico investigador principal del Centro de Observación de Ciencias de la Tierra. en la Universidad de Colorado-Boulder.

Las temperaturas en el Ártico están aumentando más del doble de rápido que el promedio mundial. Los procesos de amplificación y retroalimentación únicos, como la rápida disminución del hielo marino, contribuyen significativamente a este calentamiento. Las consecuencias del calentamiento del Ártico serán de gran alcance en todo el hemisferio norte.

El Ártico de rápido calentamiento ha comenzado a pasar de un estado predominantemente helado a un clima completamente diferente, según un nuevo estudio completo de las condiciones del Ártico realizado por científicos del Centro Nacional de Investigación Atmosférica (NCAR).

«La tasa de cambio es notable», dijo la científica del NCAR Laura Landrum, autora principal del estudio publicado en Nature Climate Change. «Es un período de cambios tan rápidos que las observaciones de patrones climáticos pasados ya no muestran lo que se puede esperar el próximo año. El Ártico ya está entrando en un clima completamente diferente al de hace unas décadas».

En el nuevo estudio, Landrum y su coautora, la científica de NCAR Marika Holland, encuentran que el hielo marino del Ártico se ha derretido de manera tan significativa en las últimas décadas que incluso un año inusualmente frío ya no tendrá la cantidad de hielo marino de verano que existía tan recientemente como mediados del siglo XX. Las temperaturas del aire en otoño e invierno también se calentarán lo suficiente como para entrar en un clima estadísticamente distinto a mediados de este siglo, seguido de un cambio estacional en la precipitación que resultará en meses adicionales en los que caerá lluvia en lugar de nieve.

Entre los observadores del hielo marino del Ártico desde hace mucho tiempo, el valor de 2020 fue significativo porque no solo marcó una disminución a largo plazo, sino también porque cayó por debajo del umbral de 4 millones de kilómetros (1,5 millones de millas) solo para el segunda vez en el récord de satélites, después de 2012, cuando la extensión mínima se redujo a 3,39 millones de kilómetros cuadrados (1,31 millones de millas cuadradas).

El momento exacto en que el hielo marino alcanza su mínimo absoluto depende de las condiciones climáticas en el Ártico, y solo se puede determinar una vez que haya pruebas claras de que la extensión del hielo marino ha comenzado a crecer nuevamente. Según la experiencia anterior, esto suele ocurrir a mediados de septiembre, aunque a veces no hasta la segunda mitad del mes.

La extensión del hielo marino se mide mediante datos satelitales, incluidos los de la NASA, el Centro Nacional de Datos de Nieve y Hielo (NSIDC) de la Universidad de Colorado Boulder, AWI, EUMETSAT OSI SAF y JAXA-NiPR. La extensión del hielo marino se define como el área donde la concentración de hielo es al menos del 15 por ciento.

PolarStern en el Polo Norte Agosto de 2020: ESPERA El rápido derretimiento del hielo fue observado en detalle por expertos a bordo del rompehielos de investigación alemán Polarstern, que es el observatorio central de la expedición de investigación ártica más ambiciosa jamás realizada y en la que participan científicos de 17 naciones.

public.wmo.int